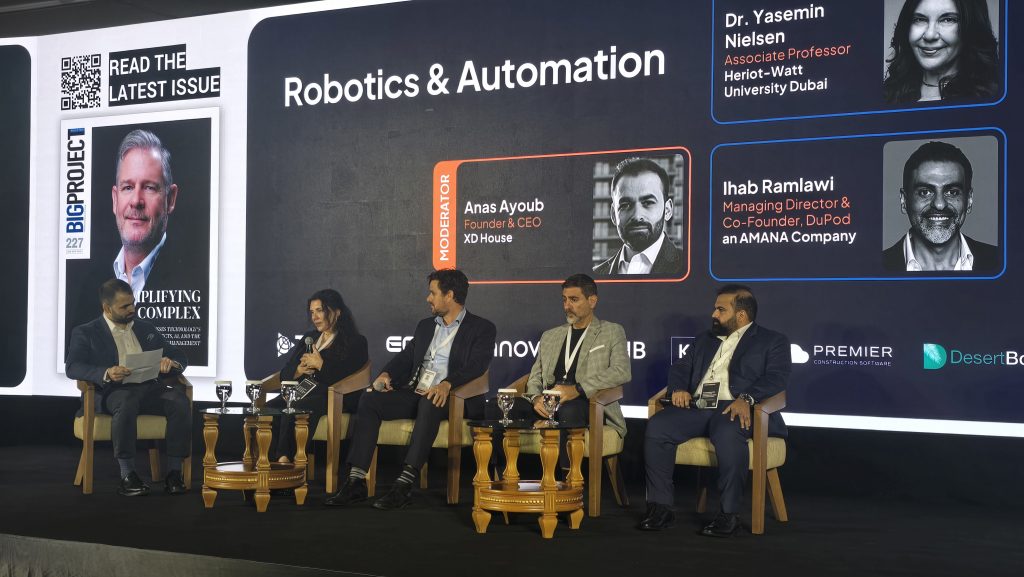

At the Digital Construction Summit, industry leaders questioned whether robotics and automation are ready to play a meaningful role in construction and manufacturing — or whether the sector still has fundamental barriers to overcome.

The panel brought together experts from academia, contracting, modular construction, and consultancy. Their observations revealed both the opportunities and limitations of applying robotics in an industry known for complexity, fragmented supply chains, and tight delivery schedules.

Douglas Zuzic, Chief Digital Officer at Innovo Group, argued that robotics should not be seen as a replacement for the workforce, but as a partner in delivering quality and safety. He cited a live project in Abu Dhabi where Innovo has been trialling a Chinese-made robot designed for floor tiling.

“We have a project in Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Lagoons, where the robot doesn’t replace labour — it complements it,” Zuzic explained. “It can lay tiles at a pace and quality that helps us meet deadlines, while our workers focus on areas that require precision or adaptation. It’s not an either-or scenario. It’s about improving quality, timelines, and safety while still working with skilled trades.”

While early trials have shown promise, Zuzic stressed that automation will not solve every problem. Large open areas may benefit from robotics, but tight or intricate spaces still rely on human labour. “We are driven by time, cost, and quality. Technology is one way we can balance those pressures and keep our people safe on site,” he said.

Modular Construction as a Natural Fit

For Ihab Ramlawi, Managing Director and Co-Founder of DuPod, robotics finds its best use in controlled environments. Modular construction shifts activities from unpredictable job sites into factories where automation can be applied effectively.

“In modular, you can monitor efficiency like in a manufacturing plant,” Ramlawi said. “But before you invest in robotics, you need standardisation and simplicity. Our goal is to create design processes that machines can understand. Think of an IKEA manual—simple maps, standardised components, and barcoded instructions for machines to read.”

Ramlawi warned, however, that the supply chain remains a sticking point. Developers often resist standardisation, demanding unique components and custom designs that undermine efficiency. “Why do we need 50 different types of bathrooms in one tower?” he asked. “If we worked with clients earlier, we could standardise, optimise materials, and reduce costs. Without that mindset shift, robotics becomes harder to implement.”

Academia and Data Challenges

Dr. Yasemin Nielsen of Heriot-Watt University Dubai added that embedding research directly into industry partnerships can accelerate adoption. Her team is working with companies that sponsor researchers to explore emerging automation and AI tools while tackling real-world projects.

“The challenge is not just in the technology,” she said. “It is in how we collect, process, and use the data that comes from construction sites. In manufacturing, data flows are consistent. In construction, the variability of projects creates barriers to adopting robotics at scale.”

Consultant Pratik Dalai of TBH stressed that piecemeal adoption will not deliver the full benefits. Instead, the industry must build an ecosystem where all stakeholders — from consultants and contractors to subcontractors and clients — engage early and consistently.

“We need to find balance between innovation and application,” Dalai said. “Pilot projects can prove feasibility, but wider adoption requires acceptance and collaboration. Innovation should not be about buzzwords; it must solve problems of time, cost, quality, and safety. That means involving subcontractors and manufacturers earlier, and building capacity across the whole supply chain.”

He also noted that contractors are increasingly leading discussions on design and optimisation — roles traditionally held by consultants and architects. “It’s a drastic shift, but a positive one,” Dalai observed. “Contractors are now shaping how projects are designed, which opens doors for automation and robotics to be considered much earlier in the cycle.”

The panellists agreed that early-stage engagement with technology providers is becoming critical, particularly as developers in the UAE and Saudi Arabia show greater openness to modern methods. Ramlawi called it “an awakening” that has begun to reshape the market.

“If a project is badly designed, it’s almost impossible to add value later,” he said. “But when we are engaged from stage two instead of stage three, we can influence design, optimise costs, and integrate modern construction methods from the start. That is where robotics and automation can really add value.”

From Potential to Practicality

The debate underscored that robotics and automation are no longer futuristic ideas for construction—they are already being trialled in live projects. Yet the path to widespread adoption requires cultural change, supply chain cooperation, and an industry-wide willingness to standardise, simplify, and collaborate.

As Dalai concluded, “It’s about creating an ecosystem where innovation and application move in step. Without that balance, robotics will remain a buzzword. With it, the industry can finally start to deliver on the promise of smarter, safer, and faster construction.”